Ethical Capitalism

Democracy 3.0Our current blend of democracy and capitalism is the wrong governance model to face humanity’s modern challenges. Governments have repeatedly proven themselves unable to react efficiently to contemporary problems. I propose a new socioeconomic model that aligns tightly the efforts of individual agents to the Common Good.

The problem

Capitalism has been responsible for the most extraordinary increase in standard of living in the history of humanity.1 We transitioned from toiling relentlessly for basic survival to enjoying more free time, luxurious food, and sophisticated entertainment than could ever be thought possible.

Democracy has led to the highest drop in inequality in our history. We went from the nobility having the right of life and death over starving peasants to the concept of middle class.

But our system is broken. While it was able to get us out of straw houses, our antiquated model leaves behind too many people, provides very little return on debilitating levels of taxation, does not represent our interests and opinions well, and has proven itself unable to solve modern challenges.

Capitalism has turned to a predatory form, where there is too little correlation between individual reward and the Common Good. The individual pursuit of wealth is not increasing common well-being anymore. Too many of the sharpest minds are turning to the highest-paying endeavors, with little positive externality. Compounded by rising inequalities2, this has led to increased resentment and class warfare that will only get worse if we do not alter our current trajectory.

The distrust of our system has led to a disappearance of shared purpose. Humans have a fundamental need for meaning and a sense of belonging to a group. For millennia, these two philosophical necessities have been fulfilled largely by religions and nations. Whether you liked it or not, you were told in no uncertain terms where you belonged, and what your life’s purpose was. Recent history has seen a decrease in religious beliefs, leaving nations as the main bearers of that responsibility. But the collapse of trust in our system has broken this last bastion and left a void that people are scrambling to fill. This is why terrorism, extremist ideologies and populists are thriving3: we cannot abide a meaningless life.

The level of discontent is so high4 that many people in the Western world have begun to relativize the actions and models of dictatorships across the world. The unhappiness in the wealthiest parts of the world is so strong that countries employing systematic persecutions, totalitarianism, and even genocides do not necessarily appear to have a drastically inferior governance system5.

This problem is so dire, so critical to the future of our civilization, that none of us can shy away from it6. If we do not change course very soon, our way of life has a serious risk of being annihilated by climate change, artificial intelligence, social upheaval or authoritarianism.

Our ruling elites have ignored the issue for decades. Not because they did not care, but because they had no idea how to solve it. The electorate, which does not dwell on the causes of the predicament, is so fed up that they started to elect whoever promised the most different path. And because none of our politicians had any clue, they did not offer any significant solution. That is of course an environment where demagogues shine. The Western World started to elect populists who also had no clue how to solve the problems, but were happy to promulgate simplistic ideas to get elected and obtain personal power.

The issue is clear. But what solutions are proposed?

The current solution

The Left’s approach

The Left tends to blame capitalism. Their solution is more regulation, more government.

Despite the rich capturing an increasing proportion of the nations’ wealth2, socialist rhetoric is failing to get a proper foothold. Why is the Left performing so poorly in an environment of increasing inequalities78? Because we have seen this movie before. We know from the examples of communist and extreme socialist countries around the world that this is not the answer. In addition, and very importantly, we distrust our governments. We know they are unable to utilize efficiently the enormous sums of money at their disposal. We have experienced too many times that more government destroys wealth, increases corruption9 and takes away freedom, under the guise of reducing inequality and increasing security.

The critical point is that the government, like any central authority, is terrible at making decisions in the interest of the Common Good. Form a committee with the smartest people on the planet to make decisions affecting the lives of millions of people, and they will get to a solution that does not work for most people. There is no way around it. The world is far too complex for any central authority to be able to solve our modern problems.

That is in fact the grand lesson of the 20th century. Why did capitalism outperform communism? Certainly not because of its ideology: communism actually feels much nicer, human and utopian than the dry free-for-all of capitalism. It outperformed because it decentralized decisions. It did not rely on a central authority. And as society delegated decisions to the individuals, they were able to make the right choices that made them personally wealthier and happier. The benefit was so strong that most countries elected the less sexy, more efficient ideology1011.

The Right’s approach

On the other side of the aisle, the Right tends to tackle our current predicament by doubling down on unbridled capitalism12. It prefers to close its eyes to the massacre free markets are causing to the environment.13 It praises the record levels of the stock markets, oblivious to the increasing poverty for an ever larger part of the population14. While there are nuances, the critical point that I take away on this side of the debate is the failure to recognize the limitation of capitalism: optimization by each individual does not lead to the optimal Common Good.

So what is the answer? Ignoring the terrible side effects of capitalism, the right-wing solution, or increasing government, the left-wing solution?

Our elites have been grappling with that conundrum, but the people intuitively understand both approaches are flawed. And the results are all-time high distrust in society and its elites15.

We absolutely need better governance of our economic system. If we are to prosper as a society, and perhaps even to simply survive, we imperatively need our collective work to lead to a good outcome for humanity. Our work cannot be detrimental to our climate, health, happiness, or well-being. It must be aligned with the Common Good. And let us stop fooling ourselves: leaving to the government the task of aligning the gigantic machinery of capitalism to the Common Good is simply delusional.

The proposed solution

A new governance model

So I would like to propose a new way, a solution that breaks free from the trade-off between greedy capitalism and incompetent government. The core of the issue is that we assigned the mission to determine what the Common Good is to a central authority, the government. This is failing in the same way that communism failed when it took on the mission to allocate the means of production. So the solution is obvious: do not ask the government what the Common Good is, ask each individual. In the same way that local optimization of personal wealth by individuals led to an overall increase in wealth, local optimization of the Personal Good will result in a much greater Common Good.

It is impossible for a central authority to quantify how much more valuable to the locals cleaning a certain beach would be versus creating a bicycle path. But that question has an obvious answer to each individual involved. So let’s simply get the government out of the question of evaluating what is the Common Good, and let’s decentralize that question.

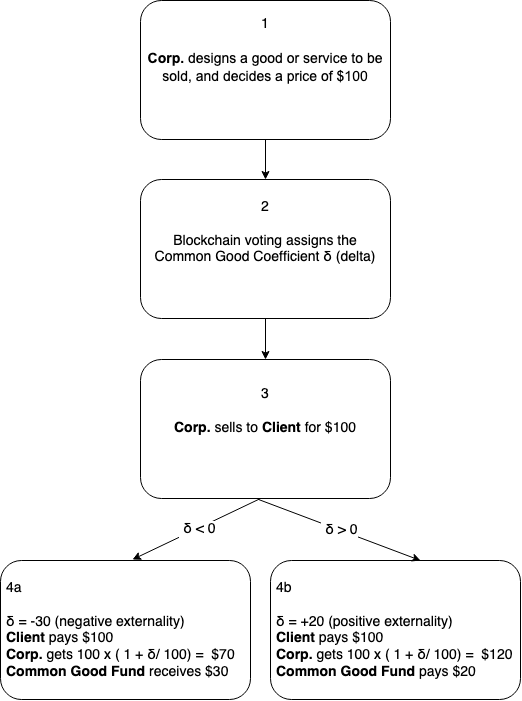

Concretely, I propose that each good or service is evaluated on how much Common Good it brings. The amount received by the seller is adjusted by the Common Good Delta. This delta is either added or removed from the Common Good Fund. The client pays the same price, irrespective of this delta, and does not even have to be aware of this mechanism.

This delta is determined by a decentralized vote. One person, one vote. When the transaction is perceived as beneficial by the decentralized vote, the delta is positive, and the seller receives an additional amount on his sale, paid from the Common Good Fund. When the transaction is perceived as detrimental to the Common Good, the delta is negative and the amount is debited from the sales price, to enter the Common Good Fund.

Illustration of the process

δ, the Common Good Coefficient, is an integer value between -100 and +∞. A positive value represents a positive externality, i.e. the transaction is beneficial to the rest of the world, outside of the client and provider. A negative value represents a negative externality.

As this project develops, the blockchain vote could evolve from a wide to narrow voting:

- wide : δ is determined for all goods and services of each firm. For example, Company X’s main business activity sells cigarettes, and is assigned a δ of -0.5 for everything it sells, even if not cigarettes. In other words, δ represents the averaged Common Good Coefficient across all the company’s goods and services.

- average : δ is determined for each type of goods and services of each firm. For example, Company X’s cigarette selling transactions have a δ of -0.8, but this company’s nicotine patch selling transactions have a δ of +0.3

- narrow : δ is assigned to each specific transaction That would allow for not only adjusting the δ to the product and the company, but also to the client. Indeed a certain type of good and service could have varying social impact, depending on who the recipient is (e.g. selling advertising slots to a charity might be seen as less detrimental than selling advertising slots to a tobacco company)

Comparison to the current model

This idea is so different from anything we know that it might sound far-fetched at first sight. But let’s compare it to the current flow from Work to Common Good.

| Centralized model (current model) | |

|---|---|

| 1. Work is performed. A good or service is sold. The government takes an amount from that transaction via a highly complex tax system, irrespective of whether the transaction is beneficial or not for society overall. | Inefficient. Companies could spend all their resources in selling something that is detrimental to the Common Good. |

| 2. Government determines what is the most urgent task to achieve for the Common Good. Is it cleaning the beach? Is it the new bicycle lane? Is it planting more trees? | Inefficient. A central authority cannot determine accurately what is the Common Good of many different individuals. |

| 3. Government spends the money to try to achieve the desired outcome. | Inefficient. Central authorities cannot be competent in many areas, and they suffer from bureaucracy and corruption. |

| Decentralized model (this proposal) | |

|---|---|

| 1. Work is performed. A good or service is sold. The price is marked up or down given its impact on the Common Good. | Efficient. Companies have direct incentive to spend their resources on something that is recognized as contributing to the Common Good. |

| 2. A decentralized vote determines whether the work performed was in the interest or to the detriment of the Common Good, and by how much. | Efficient. The collective will of individuals is computed directly, specific to the transaction, rather than represented by the government elected on many criteria several years ago. |

| 3. There is a direct incentive for companies and individuals to perform work that is aligned with the Common Good. | Efficient. Companies and individuals can focus on the subset of tasks that they are good at. |

The proposed model radically improves two distinct issues: the determination of the Common Good (what it is), and the practical enactment towards reaching the determined goals (how to achieve it). Rather than having a central authority decide what the population needs and contract companies to work in that direction, this decentralized model ensures that all companies organically work towards the Common Good. This is a mindset revolution, the fiduciary duties to maximize shareholder value is thereby aligned tightly with what is good for society at large.

Dynamic pricing

Of course, the decentralized votes are held regularly, and deltas adjust. The flows in and out of the Common Good Fund need to balance out to 0. At the beginning of the implementation of the model, many transactions are being voted as working against the Common Good, so they pay for the ones that are voted as good. Over time, fewer and fewer transactions are actively against the Common Good. Some remain, as humans have some bad habits they are willing to pay for (e.g. smoking). But even among the good transactions, some are voted as more strongly beneficial than others, and so over time, a negative delta is applied to the prices of transactions that are beneficial, but not sufficiently so. This ensures naturally that individuals spend their effort on the most valuable tasks for the Common Good.

Analysis

Self-interest

The beauty of this proposal is that it still relies entirely on individual self-interest. As we can see in our society, the public shaming of CEOs for the evil behavior of their companies has little to no impact. While it is a beautiful ideal, like communism was, trying to elevate individuals’ moral standards is doomed to fail. This proposal does not try to change human nature, but simply makes sure we align self-interest to common interest.

Imagine a world where the brightest minds do not compete to be lawyers, traders and lobbyists, but nurses, environmental scientists, beach cleaners, or whatever is voted the most beneficial for the greater good by the actual people. Imagine if the smartest entrepreneurs in the world were building CO2-capturing technologies instead of soul-destroying, addictive social media. Imagine a world where we feel we benefit from the success of others, where we are all in the same team. Imagine if envy is replaced by collaboration.

Humanity has an immense talent, we are the most clever we have ever been, we innovate at the fastest pace ever… And yet nothing we collectively agree to be the most important gets done. Governments are clearly failing. It is high time we change this absurdity by aligning our work to the Common Good.

And as an added bonus, all of our work will become much more meaningful. We will know for certain whether, and by how much, we contribute to the Common Good. It is hard to be happy to pay taxes, not only because we have little trust it will be put to good use, but also because there is no correlation between the tax taken and the Common Good. Taxes are the same for all transactions. Establishing a direct link between prices and the Common Good will make our contribution much more tangible, and therefore our work more meaningful.

Decision-making with many agents

Quantifying the externality - the Common Good - of a transaction is a very hard problem. That is why a government, as a central authority, is unsuccessful in doing so, despite being well-informed. The right process leverages multiple partially informed agents voting to quantify it, not only because the agents themselves are the third parties directly impacted, but also because this paradigm is the most effective one in this type of situation.

Mathematically, there is a parallel to be drawn with the ensemble methods in Machine Learning. When trying to quantify a difficult phenomenon, this type of technique groups together a large number of simple models. This has proven more effective in many cases than using a single sophisticated model.

Democracy 3.0

Democracy is in decline, as evidenced by the gradual decrease in voter turnout since the 1980s16. This is due in large part to the increasing number of ideologies: nations gradually became less politically uniform, and an increasing number of voters felt unrepresented by their elected officials. Even when their preferred politicians were in power, individuals did not feel aligned on all, or even most, of their positions.

The other major contributing factor is our shared reflex to elect the loudest, brashest among us as our leader. This makes sense, as this is what our species has been needing for 97.6% of our existence, if we consider a lifespan of 233,000 years 17, and a civilized milestone placed 5,500 years ago18. While our cortices know we now need brainy leaders, our reptilian brains make it hard for us to select them19.

So what are the solutions? Relying on a democratically elected individual has failed. Counting on an autocratic head of state is even worse. Appointing AI-powered robots as our leaders, as some companies are currently opting for20, seems unwise21.

The proposed model of decentralized voting can reignite citizens’ interest by creating a much more direct form of democracy, whereby voters can express a much fuller range of their sensitivities. It also does away with the reliance on single individuals, and empowers our shared wisdom instead.

Conclusion

There are many issues to solve to get this idea to a practical implementation. I cannot solve this alone, and it would not make sense for me to do so even if I could. So join me if you believe this project has a chance of making the world a better place for us all.

Cynthia Taft Morris (1995), How Fast and Why Did Early Capitalism Benefit the Majority? ↩︎

Gabriel Zucman, Annual Reviews (2019), Global Wealth Inequality ↩︎ ↩︎

Séraphin Alava, Divina Frau-Meigs, Ghaydahttps Hassan, UNESCO (2017), Youth and violent extremism on social media: mapping the research ↩︎

Lee Rainie, Andrew Perrin, Pew Research Center (2019), Key findings about Americans’ declining trust in government and each other ↩︎

Sarah Repucci and Amy Slipowitz, Freedom House (2022), The Global Expansion of Authoritarian Rule ↩︎

Jonathan Perry, United Nations (2021), Trust in public institutions: Trends and implications for economic security ↩︎

Marie Pouzadoux, Le Monde (2022), Worst presidential election result in the history of the Parti Socialiste ↩︎

Carl Baker, Elise Uberoi, Richard Cracknell, House of Commons Library (2019), General Election 2019: full results and analysis ↩︎

World Bank (2021), Combating Corruption Brief ↩︎

Nikki Haley, Wall Street Journal (2020), This Is No Time to Go Wobbly on Capitalism ↩︎

Ari Drennen, Sally Hardin, Center for American Progress (2021), Climate Deniers in the 117th Congress ↩︎

Jonnelle Marte, Reuters (2020), Trump touts stock market’s record run, but who benefits? ↩︎

OECD (2021), Trust in Government ↩︎

Abdurashid Solijonov, Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (2016), Voter Turnout Trends around the World ↩︎

Celine Vidal, Christine Lane, Asrat Asfawrossen et al., Nature (2022), Age of the oldest known Homo sapiens from eastern Africa ↩︎

National Geographic, Key Components of Civilization ↩︎

Hemant Kakkar, Niro Sivanathan, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2017), When the appeal of a dominant leader is greater than a prestige leader ↩︎

NetDragon Websoft Holdings Limited, PRNewswire (2022), NetDragon Appoints its First Virtual CEO ↩︎

John Wills, National Film Registry (1984), The Terminator ↩︎